Press release by GEOMAR - Helmholtz-Zentrum für Ozeanforschung Kiel.

The strongest climate fluctuation on time scales of a few years is the so-called El Niño phenomenon, which originates in the Pacific.

A similar circulation pattern exists in the Atlantic, which scientists under the leadership of GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel and involving researchers from Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research (Norway) and JAMSTEC (Japan) have studied in more detail. Their results, now published in the international journal Nature Communications, contribute to a better understanding of this climate fluctuation and pose a challenge for prediction models.

El Niño, or more correctly El Niño - Southern Oscillation (ENSO), cause significant warming of the eastern Pacific, accompanied by catastrophic rainfall over South America and droughts in the Indo-Pacific region. Powerful events have global effects that reach even into the extra-tropics.

There is also an El Niño variant in the Atlantic, called the Atlantic Niño, which, for example, has effects on rainfall in West Africa as well as the development of tropical cyclones over the eastern tropical Atlantic. A better understanding of the poorly investigated little brother of the Pacific El Niño in the Atlantic could potentially improve climate forecasts in the region. The study now provides first results and suggests useful predictability of the Atlantic Niño.

“The Atlantic Niño, like its Pacific counterpart, exhibits a characteristic asymmetric structure in the changes of sea surface temperatures and surface winds from east to west, with the strongest warming occurring in the east. However, there are some differences: the Atlantic events are of smaller magnitude, shorter duration and less predictable, but the reasons for these differences are not fully understood”, explains Mojib Latif from GEOMAR, co-author of the study. The researchers used data from various sources, including in situ observations, satellite and reanalysis products.

Unlike the Pacific El Niño, which typically lasts for a year, the Atlantic Niño is limited to just a few months. The team of scientists have now been able to decipher the cause.

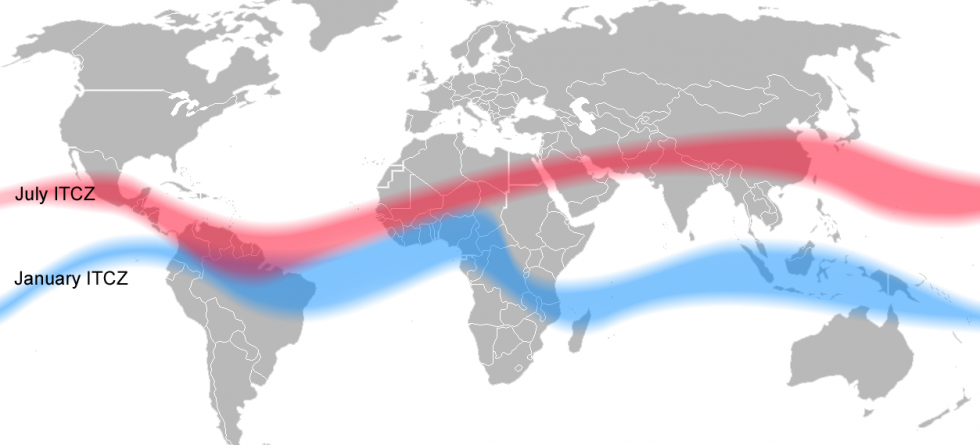

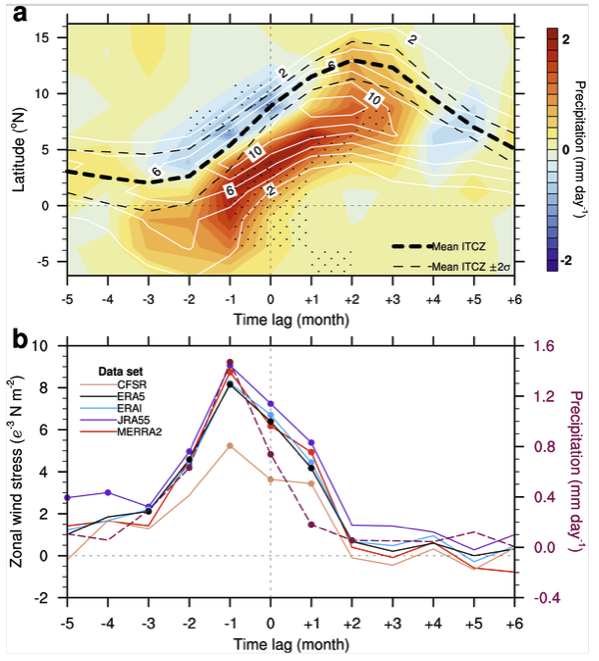

“In our analyses, we identified the movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), a band of heavy rainfall stretching across the tropical Atlantic, as the reason”, Latif continues.

“The seasonal migration of the ITCZ has a significant influence on the interaction of sea surface temperature with the overlying atmosphere. Only when the ITCZ is very close to or over the equator the interaction is strong enough to cause large climate changes”, explains Hyacinth Nnamchi, lead author of the study.

“Or put another way: The fluctuations in sea surface temperature during the Atlantic Niño are not strong enough to keep the ITCZ at the equator, as in the case of its Pacific big brother”, Nnamchi continues.

The authors intend to use their new findings to represent the ITCZ more realistically in climate models in order to enhance prediction of tropical precipitation. “The ultimate goal is seasonal climate forecasts that enable, for example, planning for agriculture and water management in West Africa”, says Latif. Unlike in mid-latitudes, this is certainly possible for the tropics, says the climate researcher.

Reference

Nnamchi, H.C., Latif, M., Keenlyside, N.S. et al. Diabatic heating governs the seasonality of the Atlantic Niño. Nat Commun 12, 376 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20452-1